Decisions are the result of applying frameworks, processes, and patterns embedded within the architecture of our brain to achieve an outcome. When you are making a decision, you will be doing so in contexts relevant to achieving your intentions. All decisions thus have an impact on the context, associated problem-finding activity, and the quality of future decisions.

Many decisions are unconsciously patterned responses to triggers from our environment, however, if you know what comes next, you are not necessarily making decisions but simply following established patterns like a trail of breadcrumbs. Conversely, you know you have made a decision when you can see that some kind of change has occurred and that something will be different because of it.

Processes used to guide decision-making are underpinned by values, beliefs, and world views. Decision-making was once considered to be a context-free, logical, step-by-step process. Increasing awareness of complexity has introduced a broader range of approaches highlighting the importance of understanding the context/s within which decisions are made.

Decisions are a result of reasoning processes usually called Deductive, Inductive, and Dialectical each of which influences how we perceive problems and approach decision-making. Deductive reasoning utilises formal logic producing conclusions dependent on an initial premise. For example: when we argue that a) all humans are mortal and agree that b) Socrates is human, it follows that c) Socrates is mortal.

Inductive reasoning begins with collecting observations which are then used to support general conclusions about the facts observed. Inductive reasoning can be rendered invalid when more information comes to light. In 16th-century Europe, it was possible to say that “all the swans I see are white, therefore all swans are white” This inductive reasoning was invalidated when Dutch sailors found black swans in what is now Western Australia.

These are familiar forms of Western reasoning. A third form of reasoning is called Dialectical and looks at ways in which conflicting and contradictory propositions can both be true. It emphasises the importance of the context and possibilities for finding a middle way between extremes and invites more flexible ways of dealing with change, conflict, and uncertainty. Decision-making contexts can be both organised and chaotic at the same time, albeit perhaps in different locations (Hock 2000). This is important for improving the quality of decision-making because it causes us to question how we are thinking about problems before we enter into decision-making processes.

Kahneman (2011) distinguished between fast (System 1) thinking which is automated, gut feeling, and intuitive, and slow(System 2) thinking, which utilises critical thinking and is conscious, deliberative, and reflective. To System 1 and 2 Webb (2021) adds System 3 employed when there is little information, and the outcome can’t be predicted. System 1 is intuitive and System 2 deliberative, while System 3 factors in consideration of long-term and downstream impacts of decisions.

Argyris and Schon (1974) examined how conscious and unconscious processes inform the decisions we make. We hold two maps in our head, one is the theory we espouse (what we say) and the other is our theory in use (what we do). For example, we may say that we support collaboration, but others may see us as behaving autocratically. We are often unaware that our espoused theory and theory in use are not the same. Effective decisions require congruence between our espoused theories and theories in use, which can be achieved by consciously challenging our underlying assumptions and finding the disconnections between what we say and what we do (a process called double-loop learning).

To date over 180 cognitive and memory-related biases which heavily influence the quality of our decision-making have been identified. These biases shape how we identify and understand the contexts in which we are working. For example, when undertaking planning tasks our bias may lead us to underestimate the time required to complete a task. At such times decision-making may be informed and constrained by our perception of time instead of real-time conditions.

The benefit of adopting different lenses or perspectives helps us to challenge the assumptions that we take for granted. Our capacity to do this is dependent on our awareness of the benefits or drawbacks of taking different perspectives. Once we reduce our dependence on familiar models, or unsuitable habits no longer relevant to new contexts, awareness can lead to the emergence of new knowledge.

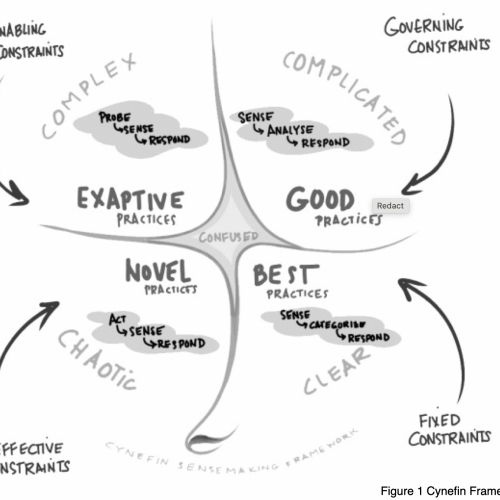

The Cynefin framework, Figure 1, proposes 5 decision-making contexts or domains identified as Clear, Complicated, Complex, Chaotic, and Confused. The framework offers a vantage point from which to view our perceptions based on specific conditions. Where conditions are orderly and therefore familiar and unexceptional guidelines rely on well know practices. Where they are unordered and therefore unfamiliar and exceptional guidelines prompt us towards new untried solutions. Where all is confusion, nothing is familiar, and there are no guidelines, an essential first step is to identify the actual nature of the immediate context before making any decisions.

Beyond this brief introduction to decision-making lies a wealth of models and frameworks whose applications can assist in improving the quality of your decisions. One resource for exploring further is ‘The Decision Book’ (Krogerus & Tschappeler, 2017).

References

Krogerus, M., & Tschappeler, R. (2017). The Decision Book. London: Profile Books.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow. Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4299-6935-2

Hock, D. (2000). The Art of Chaordic Leadership Leader to Leader, a publication of the Leader to Leader Institute. Retrieved from http://www.meadowlark.co/theartofchaordicleadership_hock.pdf

Snowden, D. J., & Boone, M. E. (2007). A Leader’s Framework for Decision Making. Harvard Business Review. November 2007: 69-76. Retrieved from https://hbr.org/2007/11/a-leaders-framework-for-decision-making.

Argyris, C., & Schon, D. (1974) Theory in practice: Increasing professional effectiveness. San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

Thaler, Richard H., Cass R. Sunstein. 2008. Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Webb, P. (2021) Systems 3 Thinking, how to choose wisely. McPherson’s printing. Australia

This article – To be published in the Encyclopedia of Project Management 2023

Decision Making Process

An overview of decision-making processes.